Nuri Mettursun died alone, five months into a five-and-a-half-year prison sentence. No family gathered around his bedside to hear his last words. His funeral was a clinical affair. No one closed his eyes gently, or bound his jaw closed, or washed him ceremonially before swaddling him devoutly in a length of white cloth. No Islamic prayers, no mourning throng crying out and jostling to carry his casket through the streets to the cemetery. No traditional wake. No gathering around the grave to send him off.

His funeral home was a hospital mortuary slab, the pall bearers, a gang of armed police who unceremoniously dispatched the 67-year-old man to a cemetery outside the city. Relatives were not invited.

This father of eight children is just one of the large number of elderly Uyghurs, some in their eighties and nineties, who have been locked up in a vast network of camps and prisons since 2016, when Chinese authorities unleashed a wave of arrests and detentions on the Turkic population of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, a region of vast deserts, mountains, and oases three times the size of France in China’s northwest.

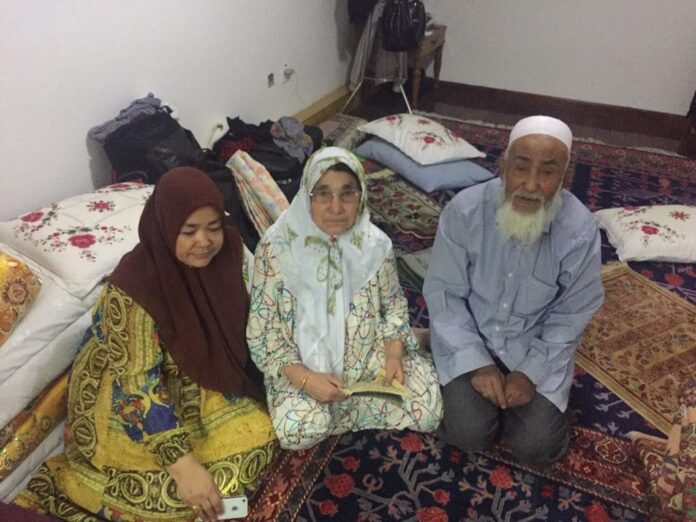

His son, Nurmemet Mettursun, told The China Project of mourning the father he lost from thousands of miles away, in Istanbul.

Among the many thousands rounded up and sent to so-called vocational training camps and jails under the iron fist of Xinjiang’s Communist Party Secretary, Chén Quánguó 陈全国 — who was promoted in 2016 from quelling dissent in neighboring Tibet — were 1,481 Uyghurs aged 55 years or older, most of whom were grandparents and retirees. These elderly Uyghurs were jailed, forced to learn Chinese, and subjected to hours, weeks, and months of CCP propaganda. They were held to be purged of “ideological viruses.”

Many, like Nuri Mettursun, have died serving jail terms. Most, like him, never knew why they were in prison in the first place. All those who didn’t make it were denied the customary Muslim burial rites. News that two detained, retired hat makers passed away recently shocked and saddened members of the exiled Uyghur community, many of whom have loved ones still in jail.

Painstaking documentation by Russian-American researcher Gene Bunin and his team at Shahit.biz (shahit means “witness” in Uyghur) gave birth to the Xinjiang Victims Database, where the details of 60,669 arrested, detained, disappeared, and deceased individuals have been collated and updated daily since 2018. The record of elderly victims forms just one of many groups of individuals buried in its pages.

Nurmemet Mettursun’s father was one of these. Five months into a jail term imposed in 2017, Nuri Mettursun was declared dead by officials from the Urumqi Number Five Prison, who called the family to identify his body. Close relatives were given a cursory look at his body before he was taken away and buried by police.

Cause of death?

“We were told ‘old age,’” said Nurmemet.

Interviewed in his traditional Uyghur medicine consulting room in a suburb of Istanbul, the 40-year-old naturopathic physician was quietly distraught. Not only was he shattered by the death of his father, but news that his 68-year-old mother, Tajinisa Yimin, was detained on terrorism charges in 2021, and that her case was still under investigation, played on his mind. Inquiries made to the United Nations last year by the Istanbul-based Chinese Concentration Camp Victims Group as to the whereabouts of members’ relatives revealed that she had been “criminally detained on suspicion of possessing items promoting extremism and terrorism” on July 25, 2021. (During the clampdown, kitchen knives were considered terrorist tools and confiscated and cataloged.) On September 11, 2021, Nurmemet’s mother was “transferred for prosecution for participating in a terrorist organization.” His sister, Muherrem Mettursun, 49, was detained at the same time. Both their cases have gone cold.

His father dead and his mother and sister disappeared, one tragedy after another dogged Nurmemet after Chen Quanguo took control over the Uyghur homeland. While he was on a business trip to Dubai in 2016, all Uyghur passports were recalled. He heard that visitors to Muslim countries were being arrested upon their return to Urumqi, taken into an interrogation room by police, then taken away. Afraid to return, Nurmemet moved on to Turkey, not knowing when or if he might ever see his wife and two children again. All contact with them ceased from that moment and six years later, he still has no idea where they are or what has happened to them.

The snippets of news gleaned via friends of friends are not good. The doors of his two homes in Urumqi, the capital of the Uyghur region, have been sealed by the authorities and his wife and children are nowhere to be found. His first child, a son, was five years old when he left for Dubai. He has never met his second child, a little brother, born on September 11, 2016, soon after he arrived in Turkey.

A pall of gloom hung over Nurmemet as he poured a cup of spicy tea with the yellow tint typical of Hotan, his beloved birthplace, deep in the south of the Uyghur region, a city at the edge of the vast Taklamakan Desert, where sand rains from the sky in the spring. The region’s large, devout Muslim families were singled out for particularly harsh treatment during the clampdowns orchestrated by Chen, who was replaced after a five-year reign of terror.

In Istanbul, Nurmemet is proud of his growing reputation among his largely Turkish clientele who come hearing of his skill in curing a variety of ailments. Success with fourth-stage cancer in several patients is one of his claims to fame, and he is immersed in penning a Uyghur medicine primer detailing his results for a Turkish audience.

He says his medical practice and writing project are all that keep him sane during his sleepless nights and days sunk in deep depression.

A grim roll call

The roll of elderly prisoners recorded at the shahit.biz website makes for grim reading.

Database number 223: Arslan Abdulla (阿尔斯兰·阿布都拉)

Age: 76-77, Male

Ethnicity: Uyghur

Sentence: 18 years

Occupation: University professor

Database number 5089: Zahidem Helpehaji (杂依旦母·咳依伯阿吉)

Age: 67, Female

Ethnicity: Uyghur

Sentence: 20 years

Profession: Medicine

Database number 7090: Saadet Bawdun

Age: 63, Female

Ethnicity: Uyghur

Sentence: 18 years

Profession: Businesswoman

Database number 9042: Abduweli Muqiyit

Age: 76, Male

Ethnicity: Uyghur

Sentence: Life

Profession: Art and literature

Database number 27805: Ablimit Mamut (阿卜力米提·马木提)

Age: 74, Male

Ethnicity: Uyghur

Sentence: 7 years

Crime: Disturbing public order

Scrolling through the thousands of names and faces is a grueling task. These statistics represent real people with families. Several have “critical” health conditions recorded. Many have partners and children also detained.

Jevlan Shermemet, 32, part of the Istanbul Victims Group, told The China Project that his 58-year-old mother, jailed for five years in 2018, possibly for visiting him in Turkey, has still not resurfaced. He came to Turkey as a student in 2011 with little interest in politics or human rights, but from the day he heard of his mother’s detention, “the CCP turned me into an activist,” he said.

“My parents were not agitators or troublemakers. My mother worked for the government in the trade and industry department for 30 years. How could she be a terrorist? But they arrested her nonetheless,” Jevlan said.

He now spends his days campaigning for his people, particularly for the release of his mother. “There are so many elderly people in prison for no reason. How can a state inflict such needless pain on people who should be at home living out their days surrounded by grandchildren?”

Rushan Abbas, the CEO of Uyghur advocacy group Campaign For Uyghurs, marked her own personal tragedy this month with the 61st birthday of her sister Gulshan, five years into a 20-year sentence for terrorism-related crimes — “crimes” that Abbas assumes are directly linked to her advocacy. Her sister Gulshan was sentenced in March 2019, but only 27 months later did the Chinese government come clean over her fate.

The retired doctor who Abbas described as having “dedicated her life to serving the Uyghur community” deserved to be “respected and cherished during her golden years.” Instead, Abbas told The China Project, she was “being subjected to harsh conditions, without regard to her health.”

Peter Irwin of the Uyghur Human Rights Project, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, denounced CCP policies of mass detention of Uyghurs as “capricious and arbitrary.” Incarcerating people in their seventies and eighties was “just cruel,” Irwin told The China Project. He accused Chinese officials of “lying through their teeth” while claiming the policies are beneficial to Uyghurs. Irwin’s research into the detention of religious figures since 2014 found 15 Uyghurs over 70 years old detained, including three over 90 years old. Irwin’s research found that Suleyman Tohti, a well-known Uyghur mullah from Kizilsu, was reportedly detained at age 86 in 2017, and subsequently died in police custody.

The catalog of elderly detainee deaths saddens Irwin, who cited the 78-year-old mother and the 80-year-old father of World Uyghur Congress President Dolkun Isa, both of whom died after being sent to camps.

Irwin further detailed the 82-year-old Uyghur Islamic scholar Muhammed Salih Hajim, who first translated the Qur’an into the Uyghur language in a government-approved project, died 40 days after being detained in late 2017 or early 2018. Then, Irwin said, there was Uyghur writer Nurmuhammad Tohti, 70 years old and suffering from health problems at the time of his detention, who died after being held in a camp for approximately five months.

Istanbul-based Uyghur journalist Musa Abdulehed Er is disturbed by the number of older detainees, many of whom are pillars of the community and leaders in their fields. Their detention shows Beijing’s purpose is “clearly to annihilate the Uyghur race,” he told The China Project. “We strongly oppose everything the Chinese government is doing to destroy our people. We will never bow to the CCP and call in the strongest possible terms on the international community to stand with us against this genocide.”

“We have hundreds and thousands of our elderly people in detention for no reasons other than their normal way of life,” said Rushan Abbas. “The thought of them being abused or neglected and deprived of the tenderness they have shown us throughout our lives is absolutely devastating,” she said. “It is time to hold the CCP accountable for their egregious and downright evil crimes and demand the immediate release of innocent victims of China’s genocide.”