The Dalai Lama, wrapped in red and yellow robes, urged chanting monks and nuns in his latest public prayers to help heal the world with their “compassionate heart”.

“Being a good human being is everybody’s responsibility,” he said, weeks ahead of Sunday’s commemorations of the failed Tibetan uprising against China that saw him flee into exile in neighbouring India.

“I urge all of you to strive towards it.”

The 88-year-old Buddhist leader says he has decades yet to live, but Tibetans who have followed him abroad are bracing for an inevitable future without him.

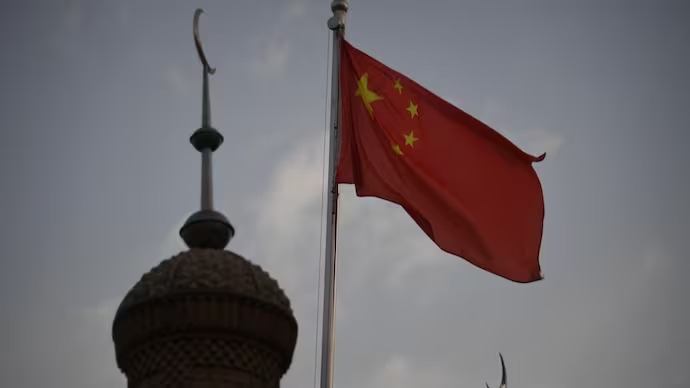

China says Tibet is an integral part of the country, and many exiled Tibetans fear Beijing will name a rival successor to the Dalai Lama, bolstering control over a land it poured troops into in 1950.

Tibet has alternated over the centuries between independence and control by China, which says it “peacefully liberated” the rugged plateau and brought infrastructure and education.

But Tsultrim, a sprightly 95-year-old Tibetan former CIA-backed guerilla, offers a warning from the past.

He recalls how he took up a gun when Tibetans rose up against Chinese forces 65 years ago on March 10, 1959, in a revolt whose crushing forced the Dalai Lama across snowy Himalayan passes into India.

Tens of thousands followed.

“We were asked to rise up to resist the invading Chinese army and to escort the Dalai Lama to exile,” Tsultrim told, dressed in a black puffer jacket, still with a soldier-like manner with close-cut grey hair and a strong handshake.

Today, he is among the last of a generation to remember what he calls a “free Tibet”, and tells younger Tibetans not to trust Beijing.

“Before Tibet lost its independence, we were herders and farmers,” said Tsultrim, who uses only one name and is based in the Dalai Lama’s adopted hometown of Dharamsala in northern India.

“Life was good, and our living was good… We had nothing to do with money, the herders sold meat and butter and farmers sold grains.”

The past

Tsultrim later joined Tibetan insurgents based in Nepal’s mountainous kingdom of Mustang in 1960, trained and supplied with rifles and radios by the CIA.

For more than a decade they snuck into Tibet to lay ambushes, including blowing up Chinese army trucks.

Dalai Lama: A portrait in pictures

“We were volunteers with our own horse, and carried our own rifle and food,” he said. “We kept waging war.”

Washington used the 2,000-strong force as a covert Cold War proxy.

But after the CIA cut funding, and the Dalai Lama in 1974 urged fighters to lay down arms and follow his call for a peaceful solution, Tsultrim left for India.

After working as a farm labourer for decades, he retired to an old people’s home near where his leader lives.

“I came to see the Dalai Lama before dying,” he said.

His comrade Ngodup Palden, 90, clings to a fading dream.

He became a paratrooper in India’s special Tibetan force for 24 years, seeing combat in the China-India war of 1962.

“Before we lost our country, we lived a comfortable life,” he said, staring out at the snow-capped Himalayan peaks that divide him from his homeland.

“It is my hope to return to a free Tibet during my lifetime,” he said, prayer beads clicking through his fingers.

“I have some hope in my heart, to be back in my homeland, my happy homeland.”

The present

Those coming from Tibet today say Palden’s hope is fantasy.

While once thousands fled to India annually, fewer than a dozen escaped last year, Tibet’s exiled government says.

Activists say Tibetans’ movements in their homeland are monitored, and that many fear arrest or retaliation against relatives should they make it out.

“I feel like a bird that has been caged for a long time and is now free to flap its wings and fly,” said 37-year-old Tsering Dawa, a former bank manager from Tibet’s main city Lhasa.

He abandoned his middle-class life in 2020 fearing re-arrest after contacting journalists about China’s “vocational training centres”.

U.N. experts say the centres are used to “undermine Tibetan religious, linguistic and cultural identity” — charges Beijing denies.

Dawa said he had been detained without trial in 2015 for nearly a year after messaging an exile group to report passport restrictions for Tibetans.

He said his detention included a brutal beating and interrogation that pushed him to “the brink of insanity”.

“I told my mother that if we stay in Tibet, we are bound to die,” he said, warning her she would be punished if he left without her.

“If we leave, there is a 50% chance of making it.”

With routes across the mountains to Nepal barred by China’s security forces, he packed a bag and posed with his 68-year-old mother as “tourists heading on holiday”.

Swallowing their terror, they smiled and snapped photographs at Lhasa airport, starting a journey that would eventually bring them to India.

In his cramped one-bedroom apartment he described leaving behind 600,000 yuan ($83,000) in his account, two houses and a car.

“The reason I got out was because of my willingness to sacrifice it all.”

The future

Younger generations who grew up in exile fear threats ahead.

“China is hell-bent on appointing their own Dalai Lama once he passes away,” said Tenzin Dawa, a 31-year-old activist.

Born in India, she heads the Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy.

She worries that the younger generations have lost hope of seeing their ancestral home.

“We grew up stateless in India… and, we never know what might happen when His Holiness the Dalai Lama passes away,” she said.

“That’s why we’re seeing a lot of emigration of Tibetans to Europe and North America.”

Tens of thousands of Tibetans have left India since 2011, according to Indian government figures.

“It is a big concern,” the activist added. “The younger generations, it is they who have to carry on the movement.”