LONDON, Oct 20- China’s real estate market is in decline. Debt deflation hangs in the air. The country’s workforce is shrinking and GDP growth is trending downwards. No wonder the International Monetary Fund at its recent shindig in Marrakech warned of slowing economic growth in the People’s Republic, raising the prospect of “Japanisation” – the prolonged economic and financial malaise that afflicted its once high-flying neighbour after an asset bubble imploded three decades ago. The trouble is that China’s economic imbalances are far worse than Japan’s in 1990. And that’s before considering the ruinous economic consequences of President Xi Jinping’s autocratic rule.

In recent decades China has followed the economic growth path pioneered by South Korea and Japan after 1945. What’s known as the Asian Development Model involves high levels of investment financed from domestic savings, relatively depressed household consumption and strong export growth. Countries which adopted this approach enjoyed many years of rapid economic growth. China’s dramatic development of recent decades conforms to this pattern. Over time, however, economic imbalances build up. Much investment turns out to be wasted and productivity growth slows. Credit-fuelled real estate bubbles appear. The economy hits a brick wall.

That’s what happened in Japan in 1990 and to several other Asian countries a few years later. China’s current position looks vulnerable as its property bubble starts to deflate. Its economy is far more unbalanced than Japan’s was at the end of the bubble economy. China’s investment is running at around 42% of GDP, some 6 percentage points higher than Japan in 1990, according to the IMF. China’s gross savings rate is 44% of GDP, 11 points higher than Japan in 1990. While Japanese household consumption exceeded 50% of GDP at the end of the bubble, Chinese households today consume just 38% of GDP.

The Japanese real estate boom is the stuff of legend. The grounds of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo were once estimated to be worth more than all the land in California. Yet China’s property bubble appears even more extreme. In the last decade, Chinese residential construction peaked at around 20% of GDP, some three times greater than Japan in 1990. Chinese real estate looks far more overvalued. At the end of last year China accounted for just over a quarter of the world’s total real estate, which had a market value of $380 trillion according to Savills. In other words, Chinese real estate in aggregate was valued at around 5.5 times the country’s GDP. By comparison, Japan’s property bubble peaked at around 4.8 times GDP.

Chinese private sector credit reached 227% of GDP at the start of this year, according to the Bank for International Settlements, some 13 percentage points higher than Japan’s 1993 peak level. It’s normally the case that richer countries are able to shoulder a greater amount of debt. Yet China’s GDP per capita has reached only half of Japan’s level in 1990. Its working age population has started to contract, as also happened in Japan some three decades ago. If China is to pay down its vast debts and avoid a Japanese-style lost decade, it must improve its allocation of capital.

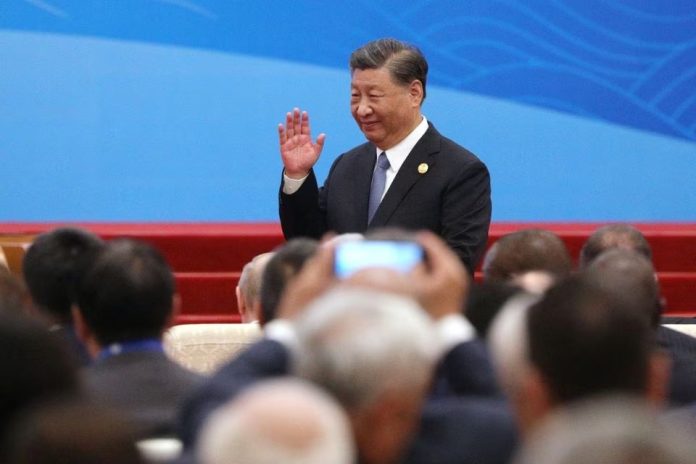

Unfortunately, under President Xi Jinping the country appears to be moving in the opposite direction. China’s economic misdirection is catalogued in Yasheng Huang’s “The Rise and Fall of the East”. Huang, who teaches at the MIT Sloan School of Management, fears that Xi is resurrecting the bureaucratic mode of government that stifled China’s economic development for centuries in the imperial era. After 1978 the authorities gave provincial governments substantial freedom to promote economic growth and rewarded them for meeting a growth target. Now Xi is clipping the autonomy of local governments. GDP targets created their own problems – not least by encouraging officials to invest excessively in infrastructure. But the alternative is worse, says Huang. Officials are now judged on demonstrations of fealty to Xi.

China’s economic miracle was created by private businesses. Beijing appears not to understand this, according to Huang. Private companies have been receiving a smaller share of bank credit, while less efficient state-owned enterprises are handed more. Xi has tormented some private industries. In late 2020 regulators suspended the initial public offering of Ant, the financial services affiliate of e-commerce giant Alibaba , (9988.HK). The following year, authorities cracked down on private tutoring companies, and tech giant Tencent (0700.HK) agreed to pay $15 billion to aid the government’s wealth distribution efforts.

Beijing has also undermined the boundaries between private companies and the state. Every company is required to set up a cell tasked with ensuring that business operations are in line with the Communist Party’s priorities. National security laws stipulate that every Chinese citizen must on request assist the intelligence services. Such requirements have undermined the trust of Western collaborators, partners, and customers of Chinese firms. When telecoms equipment maker Huawei proclaims that it is a private company, fewer and fewer foreigners are persuaded. President Xi’s encouragement of aggressive “wolf warrior” diplomacy and sabre-rattling towards Taiwan have further undermined Western inclination to do business with China. This week Washington tightened controls on exports to China of advanced semiconductors used in artificial intelligence.

After its bubble economy collapsed, Japan suffered three banking crises and a proliferation of zombie companies. Japanese firms became notorious for their low returns on capital. At least, unlike their contemporary Chinese counterparts, they remained recognisably private entities ultimately controlled by shareholders. Nor did Japan threaten the global trade system while its firms remained free to export, exchange technologies and acquire Western companies. Japanese society remained cohesive during the lost decades. Social unrest is much closer to the surface in Communist-ruled China.

China has for decades defied predictions of impending economic collapse. But the engines of the country’s growth – the private sector, globalisation and the decision-making autonomy of regional governments – have been impaired by Xi’s actions, says Huang. The real estate collapse, instigated by Beijing’s belated attempts to deflate the bubble, has brought China closer to the edge. After 1990, Japan’s banking system was slow to resolve its bad debts. This week, Beijing ordered state-owned banks to roll over local government debt with longer terms at lower interest rates.

Japan’s share of global GDP went from 17% in 1990 to 7% over the following couple of decades. On its current course, China’s economy is heading in the same direction.