On June 3, 1989, the Chinese government sent tanks, armoured vehicles, soldiers and armed police to clear Tiananmen Square, which is among the world’s largest public spaces, and its periphery off protesters and bystanders. A large number of people were killed overnight and until next evening.

Thousands had gathered from across the country in the weeks leading up to the crackdown to demand political reforms, support the protests or witness what turned out to be one of the 20th century’s most significant events. The Communist Party of China has since done a lot to keep any challenge to its rule, even notional, at bay.

China has witnessed a vigorous crushing of civil liberties over the past decade. India saw the freedoms of speech and faith come under strain during a similar period. While the two countries cannot be compared on this matrix, India could heed the lessons from China.

This year, the Hong Kong police detained an artist for drawing “8964”―a reference to the date of the Tiananmen Square crackdown―in the air. Others were arrested for gestures such as turning on their phone torch, associated with a vigil that is no longer allowed. The commemoration is barred in China. Under a national security law following the pro-democracy protests in 2019-20, Hong Kong is being made to resemble the mainland. Thousands, mostly youth, were arrested after that. Tiananmen Mothers, an NGO of the families of students killed that summer in Beijing, are not allowed to grieve in public.

So far, the party has termed the Mao-era Cultural Revolution (1966-76) a turbulent phase. It has not acknowledged 1989 more than a “political incident”.

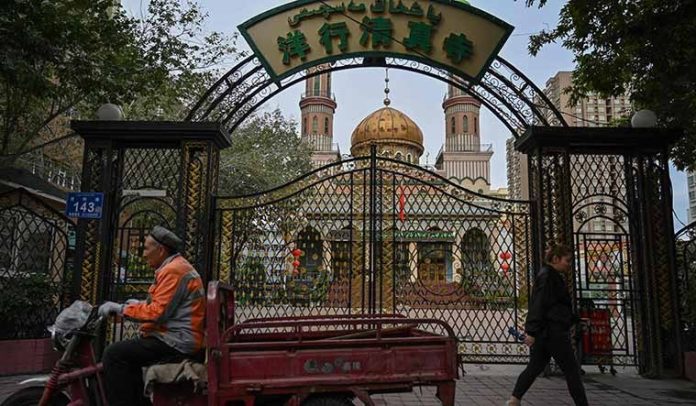

Maya Wang, interim China director at Human Rights Watch, a US-based global NGO, described the condition of civil liberties in today’s China as “dystopian”. “Things have gotten worse since Xi came to power in 2012,” she said. “The deepening repression is particularly significant in Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong.”

Earlier, for instance, “people from Tibet could escape to India,” she said, now that is impossible. Wang gave an example of “how people are being treated”. A Tibetan monk had donated money to Nepal’s post-earthquake (2015) recovery. He forgot his mobile phone in a public place. A good Samaritan took it to the local police who tracked down the monk and detained him, because he had contacted foreigners.

“The direction of civil liberties in India is not going well,” Wang said before votes in the Lok Sabha elections were counted on June 4. “But it is important for civil society ―people and activists―to communicate with each other.”

Wang said India had a responsibility to itself and the world, as the world’s largest democracy, to not just stay on course but do better on civil liberties. “Because India and China have different systems, the mechanisms of both control and resistance are also different.”

PARTY SUPREMACY

After years of totalitarian control in Mao-era China and the damage to the party’s credibility caused by the Cultural Revolution, there was a phase when independent writing, filmmaking and online publishing were not actively discouraged by the government. “It was a good time for civil liberties,” said Ian Johnson, a Pulitzer-winning journalist who covered China in the past, about the 1980s, 1990s and some part of the 2000s. The atmosphere, perhaps, also led many to mistakenly believe that the Tiananmen Square protests would succeed.